"Natcons" and "Freecons" and Liberals

Instead of trying to re-fuse conservative fusionism, let's reclaim liberalism.

I just posted this on my main newsletter, The Tracinski Letter, but given the relevance of the topic to Symposium, I thought I should also post it here. My apologies to those who are on both lists.—RWT

After watching conservatives repeatedly step on a rake on the issue of race for the past few years—and after realizing, during the Trump years, how deeply the movement has been infiltrated by the racist “alt-right”—I have long been intending to write a piece examining what makes conservatism so susceptible to this kind of influence. I finally got a chance to do it, for Discourse, under the heading “Does the Right Have a Racism Problem?”

First, let me be clear that I have anticipated what I think will be most readers’ immediate reaction.

For many on the left, this would not even be a question. Of course those right-wingers are all a bunch of racists. This has been their favorite accusation against anyone they don’t like for half a century. Such was the moral authority won by the civil rights movement that there was an irresistible temptation to try to harness that authority for every cause of the left…. Let’s just say that Godwin’s Law exists for a reason.

All of this has had a “boy who cried wolf” effect, leading many on the right to reflexively reject any accusation of racism.

We have a kabuki theater we’ve built up where the left throws around accusations of racism every time they want to win an argument (or at least end it), and the right responds by dismissing even real and obvious cases of racism as false accusations. We need to get beyond that.

I have to say that a few years back, before 2016, I also would have generally dismissed accusations of racism on the right and viewed it as rare and insignificant. That’s why this piece begins by building up a pretty thorough case that it has become a less rare and has begun to have a real impact on mainstream conservatism. I look at the influence of the “Groypers,” a small and seemingly pathetic group of white nationalists who have nevertheless managed to worm their way into positions of influence throughout the Republican Party. I also look at the persistence in conservative media of the reactionary Great Replacement theory and praise for an outright racist novel, The Camp of the Saints. (That includes in The Federalist in 2016, something I missed at the time.)

It’s not a complete and comprehensive list, but it’s enough to give you the sense that conservatives really do have a problem.

I begin the piece with Alabama Senator Tommy Tuberville professing to be stumped about whether white nationalists are racists and thereby violating the Indiana Jones Rule (which I formally define here for the first time). But these examples are coming so thick and fast now that as this piece was going to press, I had to add the latest rake-stepping: new Florida public school education guidelines that seem to blame both sides for the Ocoee Massacre and try to find a positive side to slavery, on the grounds that some slaves “developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

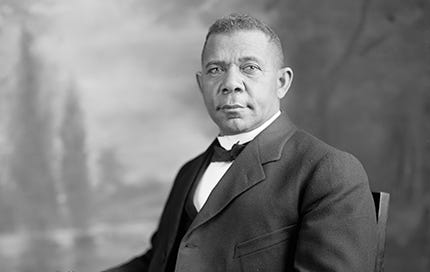

Jonathan Last lampoons this as the idea that slavery was “vo-tech for black people.” But the most damning entry in this debate is the Florida Department of Education’s own defense of these standards, which cites 16 examples of black teachers, inventors, and entrepreneurs who supposedly gained their skills under slavery. But many of these examples are wrong as a matter of historical fact, including men who were born to free blacks and never enslaved. The one that stood out most obviously to me was Booker T. Washington, who acquired his education only after being emancipated at the age of 9 at the end of the Civil War. Frankly, if they’re going to cite Washington, I’m surprised they didn’t cite Frederick Douglass because he taught himself to read while he was still a slave, despite the fact that doing so was illegal under the antebellum regime.

This makes the case against the Florida reforms far more effectively than its critics could have done.

So what is it in conservatism that makes this possible? The problem, I argue, is inherent in the very name “conservatism.”

Conservatism is a term with several possible meanings. It can mean a desire to preserve [specific] ideas and practices—such as the liberal Enlightenment ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Or conservatism can mean a suspicion of or even an outright aversion to change….

Yet by choosing not to define what they want to conserve in terms of universal principles, these “low-openness” conservatives have to ignore the most interesting and profound aspects of the Western tradition and define it instead in the most concrete and superficial ways. Consider the litany of complaints from this ultra-traditionalist wing of conservatism. They are united by the belief that everything will fall apart if it isn’t maintained in what amounts to a glamorized, idealized version of 1955. The buildings should all look the same (“neoclassical” architecture); the housing should be that of a 1950s suburb (mandated through single-family zoning); the economy should be the same (industrial factory jobs); the family structure should be the same (a male breadwinner); religion should be the same; and so on.

If trying to preserve America as a museum of the golden age of black-and-white television is their goal, it makes sense that they would want the demographics to be the same, too. This is what lures so many conservatives into expressing sympathy with those whose main complaint is that white people are no longer an overwhelmingly dominant majority. This is a simpleminded brute’s version of conservatism, yet it doesn’t lack for adherents.

For as long as I can remember, I have heard conservatives complain that the left is “too ideological.” Well, this is what happens when we get a version of conservatism that is so anti-ideological that it becomes completely blind to universal ideals.

This “simpleminded brute’s version of conservatism” is not the only one, though it has begun to dominate in recent years with the rise of “nationalist” conservatism. That’s why I was very happy to see a big new effort to push back by way of a manifesto of “freedom conservatism,” signed by some people who will no doubt be familiar to readers of this newsletter, including Charles C.W. Cooke, Jonah Goldberg, Brent Orrell, Dalibor Rohac, Charlie Sykes, and the venerable George F. Will—basically the entire classical liberal wing of conservatism. They are now apparently calling themselves “freecons” to distinguish them from the “natcons.” See an explanation from one of the signatories (which is most notable for some interesting things he has to say about the importance of the Northwest Ordinance and its role in shaping American ideals).

The manifesto harks back explicitly to the Sharon Statement of 1960 that formed the late 20th Century conservative movement in a “fusion” of free marketers, Cold War hawks, and religious conservatives. In effect, they too are trying to go back to 1955, not concretely but ideologically.

That’s a much better goal, and good luck to them. But I am not a conservative, and I am skeptical about the idea that we can solve problems just by turning back the clock.

There is a reason conservative fusionism became unfused in such spectacular fashion in the last few years. Instead of trying to rebuild the old movement with the same basic flaws, we need to make a clean break in terminology, and in our underlying priorities and ideas, and build on the firmer foundation of liberalism.