The Case for a Free-Market Welfare State

This is a contribution to Symposium No. 1, our invitation to explore and explain the basic principles of a liberal outlook.

“The perennial gale of creative destruction,” wrote the economist Joseph Schumpeter, “is the essential fact of capitalism.” For new industries to rise and flourish, old industries must fail. Yet creative destruction is a process that is rarely—if ever—politically neutral; even one-off economic shocks can have lasting political-economic consequences. From his vantage point in 1942, Schumpeter believed that capitalism would become the ultimate victim of its own success, inspiring reactionary and populist movements against its destructive side that would inadvertently strangle any potential for future creativity.1

Yet most developed countries have eluded Schumpeter’s dreary prediction, and they have done so by combining free markets with robust systems of universal social insurance. As one survey of national elections across Europe found, “the universal welfare state” directly depresses the vote for reactionary political parties.2 Conversely, I argue that the contemporary rise of anti-market populism in America should be taken as an indictment of our inadequate social insurance system3 and a refutation of the prevailing “small government” view that regulation and social spending are equally corrosive to economic freedom.

The universal welfare state, far from being at odds with innovation and economic freedom, may end up being their ultimate guarantor.

The fallout from China’s entry to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 is a clear case in point. Cheaper imports benefited millions of Americans through lower consumer prices. At the same time, Chinese import competition destroyed nearly two million jobs in manufacturing and associated services—a classic case of creative destruction.4 Yet rather than help those workers adjust, our social insurance system left them to languish. In the regions of the United States most exposed to import competition, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) was more than twice as responsive to the economic shock as unemployment insurance and Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) combined, even though it is one of the most restrictive disability programs in the developed world. Indeed, while critics of the welfare state often argue the United States spends a trillion dollars a year on social programs, only about a quarter of this comes close to anything resembling cash or quasi-cash income support—about the same annual amount spent subsidizing employer-based health insurance.

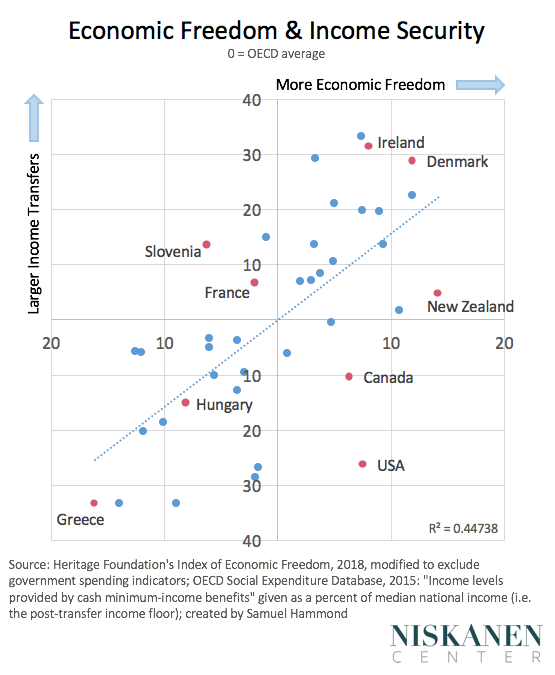

As shown in Figure 1, this has made the US income security system one of the stingiest in the developed world. As a result, the “China Shock”5 fueled a subsequent growth in anti-trade and nativist sentiment that, researchers have since shown, directly contributed to increasing political polarization, the election of nativists to Congress,6 and the populist presidential candidacies of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump.7

Figure 1: America’s Missing Income Security System

While the impact of the China Shock is easy to see thanks to its discrete timing and regional concentration, creative destruction of a similar magnitude is a continuous fact in any growing economy. In fact, in the decade after 1999, nearly four times as many American manufacturing jobs were lost to automation and productivity growth as to Chinese trade—despite this being a period with historically sluggish productivity growth and job destruction rates.8

With far bigger technological disruptions on the horizon, from robotics to revolutions in artificial intelligence, preserving the full dynamism of the US economy will require transforming the current patchwork of means-tested programs into a system premised on the fundamental complementarity of free markets and universal social insurance—a true “free-market welfare state.”

The Freedom That Matters

In the classical liberal conception, liberty is about being the author of one’s own life, free from domination. The market advances freedom by providing individuals with a mechanism to harmonize their values and interests with those of others, and to execute their plans according to their own ends. In this sense, a regulatory intervention or statute that actively precludes a particular life course or mutually beneficial exchange, like rent control or occupational licensing, impinges on personal autonomy (and, often, economic efficiency) in a way that a universal social insurance program, financed by a general system of taxation, does not. This difference allows us to define two different approaches to addressing issues of economic insecurity: “the interventionist state” and “the social insurance state.”

The libertarian economist F.A. Hayek made a similar point in a coda to his famous book, The Road to Serfdom. At the time of its original publication in 1944, Hayek noted that

socialism meant unambiguously the nationalization of the means of production and the central economic planning which this made possible and necessary. In this sense Sweden, for instance, is today very much less socialistically organized than Great Britain or Austria, though Sweden is commonly regarded as much more socialistic.9

While Hayek didn’t advocate for the adoption of Swedish-style welfare policies, his distinction between a state engaged in central economic planning and a state that provides social insurance according to general rules forced him to admit the latter was fully consistent with a free society:

Where, as in the case of sickness and accident, neither the desire to avoid such calamities nor the efforts to overcome their consequences are as a rule weakened by the provision of assistance—where, in short, we deal with genuinely insurable risks—the case for the state’s helping to organize a comprehensive system of social insurance is very strong. There are many points of detail where those wishing to preserve the competitive system and those wishing to supercede it by something different will disagree on the details of such schemes; and it is possible under the name of social insurance to introduce measures which tend to make competition more or less ineffective. But there is no incompatibility in principle between the state’s providing greater security in this way and the preservation of individual freedom.10

The contrast between contemporary Sweden and Venezuela provides an updated illustration of Hayek’s point. While both are often described as “social democracies,” their regimes could not be more different. Through the 19th and 20th centuries, Sweden designed social policies based on a notion of “the people’s insurance.”11 Universal, flat-rate social insurance schemes, from child allowances to old age pensions, were created in the backdrop of a highly capitalistic economy, including privatized natural resources and liberalized trade. As a measure of this combination’s success, in the century between 1870 and 1970 Sweden grew 70 percent faster than the United States and went from being one of the poorest countries in Europe to having the world’s fourth-highest GDP per capita.12

Venezuela, in contrast, has been pushed to the brink of famine thanks to Hugo Chávez’s (and now Nicolás Maduro’s) vision for “Socialism of the 21st Century.” This explicitly anti-capitalist ideology inspired the Chávista regime to go to war on economic liberty by nationalizing industry and natural resources, instituting wage and price controls, and enacting all manner of ad hoc, top-down, and choice-restricting legislation. Call Venezuela the “interventionist state” in contrast to Sweden’s “social insurance state,” or call it something else. Even the most ardent libertarian ought to recognize that, of the two approaches, Sweden’s generous welfare state is far superior from the perspective of personal and economic liberty—high Value Added Taxes notwithstanding.

The economic malaise that visited Sweden in the 1970s and 80s is a within-country case study of the same point. Following the 1973 oil crisis and the stagflation that ensued, a political tumult in Sweden pushed the country in a left-populist direction. Top-down labor market regulations proliferated, marginal tax rates spiked, struggling industries were subsidized, mercantile monetary policies were employed to prop up the export sector, and for a brief period corporate profits were socialized under the pretense of “economic democracy.” As a result, private investment tanked, economic growth stalled, and deficits ballooned.13 Sweden’s economic dysfunction ultimately culminated in a major recession and banking crisis in the 1990s, a reckoning that only underscored the need for major reforms. Subsequently, Sweden significantly re-liberalized its economy while keeping its social insurance state largely intact, helping it to once again become an outlier in terms of economic freedom.14

It is one thing to admit that the social insurance state is better for economic freedom relative to some other, abjectly worse alternative. It’s another thing entirely to reconcile the fact that social insurance states like Sweden and Denmark routinely score near the top in rankings of personal and economic freedom, even when such rankings are constructed by conservative and libertarian organizations that stack the deck against a high-tax-and-spend approach to fostering an open society.15 For a Hayekian this makes perfect sense: Central planning is an enemy to freedom because it does damage to the individual’s capacity to plan for him or herself.16 Social insurance, in contrast, exists to enhance an individual’s capacity to plan by imposing a degree of certainty on future states of the world.17 The societal value of social insurance is thus not unlike the societal value of rule-bound monetary policy, property rights, or the rule of law. In each case, the institution evolved to provide a level of social continuity—whether in terms of stable prices, secure ownership and contract, or “regulatory certainty”— needed for more specialized and complex economic coordination.

Toward a New Political Spectrum

The common conflation of high taxes and public expenditure with “big government” in the sense of regulatory overreach and central planning is mistaken but not surprising. As social animals, we depend on simplifying heuristics to sort friend from foe. Ideological alignment thus has far more to do with “mood affiliation” than coherent policy groupings.18 When we see someone railing against lazy bureaucrats, draconian regulations, and the “takers” who exploit the “makers,” for example, we assign to him or her an “anti-government mood,” rather than decomposing the issue into its constitutive parts.

If you support action on climate change, for example, you’re also more likely to support recycling laws. Although the two issues couldn’t be more different in their specifics, they share a common “pro-environment” mood that predicts affiliation far better than any sober analysis of costs and benefits.19 A strong belief in human-caused climate change, though justified, may not even be well correlated with knowledge about the very basics of climate science.

This becomes a major problem at the level of political affiliation since, as a rule, there is no abstract reason for the kinds of policies that clump together according to disposition to reflect stable political-economic equilibria. Instead, stable regimes are forged by historical circumstance and reinforced by actors with an interest in maintaining the status quo.

The dilemma created by the mismatch between mood affiliation and actual political-economic outcomes can be illustrated in a multi-axis model of political ideology that makes an explicit distinction between light-touch social insurance and heavy-handed market interventions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ideological sorting v. Real world outcomes

“Anti-market” in this context refers to things like intrusive, statutory labor market and business regulations, trade protectionism, nationalization, and ad hoc industrial policies—all of which are recognizable populist reactions to real and perceived economic insecurity, and conceivably substitutable with a more general tax and transfer scheme.

The traditional ideological spectrum runs diagonally from the bottom right, “libertarian” or anti-government quadrant (pro-market, anti-transfer), to the top left, “social democratic” or pro-government quadrant (anti-market, pro-transfer). Orthogonal to the traditional spectrum are what could be thought of as the “reactionary populism” and “free-market welfare state” quadrants. Reactionary populists leverage resentments against foreigners and other perceived “takers” to justify restricting transfer programs, closing the border, and intervening in the economy to the benefit of particular firms or interest groups. Of the four, the free-market welfare state is closest to the economics textbook: lightly regulated markets with insurance schemes that compensate the losers from creative destruction.

The world’s developed economies can be plotted according to the multi-axis model described above. As shown in Figure 3, a positive economic freedom score indicates above-average openness, rule of law, and regulatory efficiency, while a positive social welfare score indicates above-average income transfers.

Figure 3: Plotting the Multi-Axis Model

A strong positive relationship between social insurance and free markets is immediately apparent. In a clear case of American exceptionalism, the United States is the country most deeply in the “libertarian” quadrant, thanks to its relatively free markets and patchwork income support system. A gradient of liberal regimes then runs from Commonwealth countries like Canada and New Zealand with average income supports to more generous systems like those in Ireland and Denmark. In the progressive corner is Slovenia, with its history of state socialism. Finally, in the farthest corner of the populist quadrant are places like Hungary and Greece with conservative-reactionary histories. Most countries involve some mix of influences, however. France, for instance, has typical income supports, but is above average in terms of dirigisme, placing it on the line between social democracy and a more reactionary model.

While history is not predetermined, the multi-axis model suggests that the current US equilibrium is unstable. In fact, measured economic freedom in the US has been slowly declining in recent years, and under the influence of an emboldened “nationalist” wing of the conservative movement, there’s a risk that the trend will accelerate towards the reactionary-populist quadrant.

The Political Economy of “Big Government”

At the level of our moral tribe, politics feels like a tug of war between the top-left and bottom-right quadrants: Right-wing austerians versus nanny-state progressives. But at the level of likely political-economic outcomes, developed economies tend to fall in a spectrum between the top-right or bottom-left quadrants.

It’s easy to see why. When social insurance states like Sweden ventured down the path of market interventionism, they nearly killed the goose that laid the golden egg, making their generous spending programs seem unaffordable relative to (off-budget) command-and-control regulations. It’s a vicious cycle that, absent liberalizing reforms, leads down the road to serfdom, as has tragically happened in Venezuela. On the other hand, unregulated, open economies that lack robust forms of social insurance are vulnerable to reactionary populist backlashes when the forces of creative destruction leave large swaths of society behind. This is particularly the case for liberal democratic regimes with multiple formal channels for transferring populist energy from grassroots to public policy.

Public choice economists argue that the internal incentives of democratic governments cast doubt on our ability to optimally address various types of market failure. But rarely is the same political-economic filter applied to the politics of austerity. After all, as the economist Peter H. Lindert once noted, Wagner’s Law—the observation that as national income grows, so does per-capita public spending—is “the most durable black box in the whole rise-of-the-state literature.”20

The leading theory behind Wagner’s Law is simply that bottom-up demand for public goods like social insurance increases with a nation’s income. Liberal democracies do a better job at meeting that public demand, which is why the exceptions to Wagner’s Law tend to be authoritarian city-states, or countries with unusually binding institutional constraints. Under the authoritarian Pinochet regime, for example, Chile had aggressive pro-market reforms and austere social policy, but not without vigorous public demonstrations. Immediately after Chile’s re-democratization in 1989, the new government “alleviated the tension by expanding the size of welfare expenditures” while maintaining an open, liberal market regime.21 Chile also expanded collective bargaining and labor rights, but still found a way to balance conflicting interests in a way that steered clear of the interventionist, state-led model that typified Allende’s socialist government.

The economist Tyler Cowen calls this the “paradox of libertarianism.” Economic liberty and capitalism make nations rich. And yet, “The more wealth we have, the more government we can afford.” Cowen blames the failure of libertarians to embrace the empirical connection between liberty and “big government” on a type of mood affiliation. “That’s why libertarianism is in an intellectual crisis today,” he continues, “The major libertarian response to modernity is simply to wish that the package deal we face isn’t a package deal.”22

In short, either we will be pulled toward a reactionary equilibrium that trades in reduced social transfers for central planning and protectionism, or we will make the market resilient to economic shocks by expanding complementary social insurance systems.

Why Universalism Matters

This raises the question of how the United States, or any country for that matter, transitions from one equilibrium to another.23 On this point, the study of economic development suggests universalism is key. Take the issue of the “middle income trap,” in which countries experience fast catch-up growth only to hit a developmental ceiling far below that of rich countries. There are many explanations for the trap, but the common theme is a failure to smoothly transition into new modes of production due to institutional constraints. The countries that avoid the middle-income trap appear to do so by making a transition away from micro-level corruption and favoritism to some semblance of rule of law. This legal transition is mirrored fiscally by a transition to relatively universal social insurance programs, replacing firm-specific bribes and kin- or guild-based support networks with general, rules-based systems of social protection.

As Mancur Olson warned, the tendency for regulations to have “concentrated benefits and diffuse costs” risks making democracies sclerotic over time, as a mosaic of rules accumulates into a substantial—and locked-in—drag on economic dynamism.24 The same can be said of niche transfer programs, ranging from agricultural subsidies to flood insurance, or the dozens of distinct federal anti-poverty programs. In the United States, means-tested programs like SNAP are thus linked with powerful retail and agricultural lobbies, despite an expert consensus that SNAP would work better as a direct cash transfer. The same goes for virtually every federal program that supplies in-kind benefits to low-income parents and children, and the particular lobbies that they simultaneously benefit. In one case, the International Dairy Foods Association lobbied intensely—and quite publicly—against adding fruits and vegetables to the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) special nutrition program, fearing that it would dilute public spending on milk products.25

Lying between means-tested and universal programs in the taxonomy of welfare states is “corporatism,” or systems in which social protections are organized at an industry or sectoral level. The rise in occupational licensing follows a corporatist pattern, for instance. As employment shifted out of unionized sectors like manufacturing and into services, licensing has risen as a kind of third- or fourth-best solution for providing workers with wage and job security. The problem is that licensing also raises prices for the rest of us, reduces service quality and competition, harms labor mobility, and limits our capacity to transition workers into productive areas of employment following an economic shock. Absent a more general system of income security, the decline of unions seems to have simply expanded the adoption of the next most expedient alternative, like shifting the air in an inteventionist balloon.26

Breaking out of these sub-optimal arrangements requires substituting the political economy of concentrated benefits with what Olson called the “encompassing coalition.” Canada’s Conservative Party, for instance, used the creation of a universal, cash-based child allowance to consolidate a number of smaller niche programs, while also heading off demand for nationalized daycare. The universality of the program and neutrality of cash in a sense “encompassed” the interests of traditional and career-oriented families—appealing both to stay-at-home moms and to those in need of day care—ensuring the program’s durability.27 In contrast, analogous “cash assistance” programs in the United States have the stigma that accompanies highly means-tested programs—a pattern seen throughout the OECD.28

Given time, the slow decay in the generality of our laws and the accumulation of regulatory kludges will push us away from the productive frontier. History suggests that avoiding the reactionary political equilibrium, and the interventionism that comes with it, will require the United States to redouble its commitment to the rule of law, including as applied to social spending. In the US context, that means discarding the prevailing understanding of welfare as merely a form of poor relief (in the case of means-testing) or industry responsibility (in the case of corporatism) and embracing the universal forms of social insurance that maximize economic freedom in a democratic context.

The case for the free-market welfare state is that economic freedom and universal social insurance are complementary. Democracies can respond to the economic insecurity generated by dynamic markets in one of two ways. Either the cooperative surplus of a productive, growing economy can be used to buoy workers in transition, or those affected by displacement will demand direct interventions in the market process itself, generating growth- and freedom-killing regulatory kludges, from occupational licensing to trade protectionism. By encompassing a wide number of competing interests, universal programs are particularly adept at reducing the demand for parochial interventions, and, when linked to prior contributions, can even mitigate the backlash against immigration.

Indeed, contrary to our usual ideological spectrum, which runs from “small government” libertarian to “big government” progressive, free-market welfare states stand out as among the freest countries on earth. Universal social insurance programs are thus not only freedom- and dynamism-enhancing in and of themselves, but appear to go together as part of a stable political equilibrium. This provides a framework for a reform agenda that goes beyond insulating markets from a reactionary backlash, to one based on social welfare policy as a tool for actively accelerating the American economy into the future.

Samuel Hammond is the Director of Poverty and Welfare Policy at the Niskanen Center.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 2010. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Routledge.

Swank, D. 2003. “Globalization, the Welfare State and Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe.” Socio-Economic Review 1 (2): 215–45.

For an in-depth examination of the economics of populism and its connection to social insurance, see: Rodrik, D. 2017, “Populism and the Economics of Globalization”, CEPR Discussion Paper #12119.

Feenstra, Robert, and Akira Sasahara. 2017. “The ‘China Shock,’ Exports and US Employment: A Global Input-Output Analysis.” https://doi.org/10.3386/w24022.

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2016. “The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade.” Annual Review of Economics 8 (1): 205–40.Cite http://nber.org/papers/w21906

Zhang, Jiakun (jack), Deborah Seligsohn, and John Seungmin Kuk. 2018. “From Tiananmen to Outsourcing: The Effect of Rising Import Competition on Congressional Voting Towards China.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3123307.

Autor, David H., David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, and Kaveh Majlesi. 2016. “Importing PoliticalPolarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure.” NBER Working Paper No. 22637.

Decker, Ryan A., John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda. 2016. “Declining Business Dynamism: What We Know and the Way Forward.” The American Economic Review 106 (5): 203–7.

Hayek, F. A. 2014. The Road to Serfdom: Text and Documents: The Definitive Edition. Routledge.

To paraphrase F.A. Hayek in The Constitution of Liberty, the modern libertarian or anarchist notion of freedom as absence of taxation and other kinds of legal interference is essentially rooted in French Enlightenment rationalism and romanticism, rather than English or Scottish classical liberalism. For more, see: F.A Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (University of Chicago, 1960), 54.

Rothstein, Bo. Social Traps and the Problem of Trust. Cambridge (UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 90.

Jörberg, Lennart. 1965. “Structural Change and Economic Growth: Sweden in the 19th Century.” Economy and History 8 (1): 3–46.

Pontusson, Jonas, and Sarosh Kuruvilla. 1992. “Swedish Wage-Earner Funds: An Experiment in Economic Democracy.” ILR Review 45 (4): 779–91.

Bergh, Andreas. 2011. “The Rise, Fall and Revival of the Swedish Welfare State: What Are the Policy Lessons from Sweden?” SSRN Electronic Journal.https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1884528.

Wilkinson, Will. (2016, January 08). “Double-Edged Denmark.” NiskanenCenter.org.

This insight is the corollary to the “economic calculation problem” that was perhaps most succinctly put by James Buchanan in the title of his essay, “Order Defined in the Process of its Emergence,” available in: Buchanan, J, Gordon, D, Kirzner, I. et al. “Readers' Forum, Comments on ‘The Tradition of Spontaneous Order’ by Norman Barry.” 1982. Library of Economics and Liberty.

The philosopher Joseph Heath argues that the most popular normative justifications for the welfare state, e.g. that it exists to solve inequality (i.e. is purely redistributive) or to meet certain communitarian ends, are wrong. Instead, he argues a historical reconstruction of the welfare state’s development points to a “public economics” justification. Social insurance programs exist to solve market failures (or to fill incomplete market) and thus share the positive-sum normative logic of the market, and other Pareto-efficient institutions. See: Heath, Joseph. 2011. Three Normative Models of the Welfare State. Public Reason 3 (2): 13-44.

Cowen, T. (2011, March 31). “The fallacy of mood affiliation.” MarginalRevolution.com

Stern, Paul C., Linda Kalof, Thomas Dietz, and Gregory A. Guagnano. 1995. “Values, Beliefs, and Proenvironmental Action: Attitude Formation TowardEmergent Attitude Objects.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 25 (18): 1611–36.

Lindert, P. H. (2007). Growing public. the story: Social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

“Political Dynamic and the Welfare State in Chile under Economic Globalization.” 2013. The Korean Journal of International Studies.https://doi.org/10.14731/kjis.2013.06.11.1.201.

T. Cowen (2013, April 23). “The Paradox of Libertarianism.” Cato-Unbound.org.

For more “design principles for a free-market welfare state,” see the paper from which this article was adapted.

Olson, Mancur. 2008. The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities. Yale University Press

“Simply adding fruits and vegetables to the WIC program probably would not have touched off the current lobbying battle. But Congress is unlikely to increase funds for the program, so adding new foods would mean cutting money for dairy.” Ruskin, G. (2015, January 22). “International Dairy Foods Association – key facts.” usrtk.org.

E. Soltas. (2014, April 18). “Occupational licensing is replacing labor unions and exacerbating inequality.” Vox.com.

Hammond, S. (2017, May 31). “What Libertarians and Conservatives See in a Child Allowance.” SpotlightOnPoverty.org.

Jacques, Olivier, and Alain Noël. 2018. “The Case for Welfare State Universalism, or the Lasting Relevance of the Paradox of Redistribution.” Journal of European Social Policy 28 (1): 70–85.